In November, HQI- and CHPSO-member hospitals enjoyed an excellent webinar on managing in-house cardiac arrest, and The Joint Commission’s focus on hospital care and monitoring processes.

The subject matter expert and keynote speaker, Stephen Sanko, MD, is currently acting chief medical officer of the Los Angeles Fire Department, co-founder of the Southern California Chapter of the Sudden Cardiac Arrest Foundation, and assistant professor of clinical (research) emergency medicine at the Keck School of Medicine, University of Southern California. Dr. Sanko is a member of the Los Angeles County EMS Agency Medical Advisory Council, chair of the LAC+USC CPR Committee (where he leads the in-hospital code response teams), and chair of the County of Los Angeles Department of Health Services (DHS) Inpatient Resuscitation Committee.

The Joint Commission’s sharper focus centers on three key initiatives:

- How the resuscitation event is documented

- How performance evaluation is conducted

- How the hospital initiates follow-up care for optimum rehab and outcomes

The aim of surviving cardiac arrest followed by a safe discharge is no longer enough. Evidence-based practices in resuscitation efforts must be applied to maximize neural function and help these patients and their families with post-resuscitative care to maintain the best outcome possible.

Dr. Sanko stressed the value of membership in the American Heart Association’s (AHA) “Get with the Guidelines” program and registry, to keep teams on top of best practices for resuscitation and aware of all the important documentation elements.

Key practices in basic resuscitation include:

- Timely recognition

- Early, uninterrupted, high-quality CPR with minimal pauses

- A chest compression rate of 100-120/minute, depth of at least 2 inches

- Allowing full recoil after each compression (No leaning!)

- Minimizing interruptions in compression to less than 10 seconds with goal of chest compression fraction of >60%

- Avoiding hyperventilation (1 breath every 6 seconds)

- Early defibrillation, early epinephrine

- Diligent post-resuscitative care

As for documentation elements, Dr. Sanko shared the three-page form that the LAC+USC hospitals now use, after consulting the AHA’s “Get with the Guidelines” recommendations for revision, and discussion in the CPR Committee. “Historically,” he noted, “Documentation has been the least desirable role on the code blue team, ends up being (done by) the least experienced person, who is either not familiar with the form, or uses the back of the nearest piece of paper.” The modern approach to documentation, however, recognizes the resuscitation form as a document, a prompter, and an order form. Proper documentation can then be used to:

- Track known/meaningful endpoints over time

- Highlight areas where the team can improve

- Benchmark performance from year to year and between hospitals within a system or between systems

- Decrease double documentation

- Reduce the risk of medical litigation

By using a form that incorporates all the recommended elements, hospital teams will be in good shape to meet the intent of the 2022 Joint Commission performance evaluation standard:

PI 01.01.01 EP 10:

“The hospital collects data on the following:

– The number and location of cardiac arrests (for example, ambulatory area, telemetry unit, critical care unit)

– The outcomes of resuscitation (for example, return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC), survival to discharge) Note: ROSC is defined as return of spontaneous and sustained circulation for at least 20 consecutive minutes following resuscitation efforts.

– Transfer to a higher level of care”

Dr. Sanko summarized this section of his presentation with these words of wisdom: “For code documentation to be accurate, complete, and useful, it must be VALUED. This effort starts with a CPR Committee that is recognized, valued, and decides to document according to AHA recommendations. The code document must be used in EVERY case where either a chest compression or defibrillation are provided. The documenter should be familiar with the form and have experience.”

Lastly, the new emphasis on post-resuscitation care is grounded in the understanding that continued care is critical to neuro-intact survival. This paragraph on the new 2022 standard from The Joint Commission’s FAQs explain the key concepts organizations need to understand regarding the new Resuscitative Services requirements.1

PC.02.01.20 -The hospital implements processes for post-resuscitative care

Policies versus Procedures or Protocols

The organization can decide whether it develops a policy(-ies), procedure(s) or protocol(s). The phrase “Policies, procedures, or protocols” in PC.02.01.20 EPs 1 and 2 is meant to convey that the organization may determine which format is used for such documents. The organization can also decide whether the processes for post-cardiac arrest care (e.g., on targeted temperature management (TTM), neuro-prognostication, cardiac arrest in the context of STEMI) will be formalized as a single policy, several policies or procedures, protocols, or a combination of several types of documents. The intent of the requirements is that interdisciplinary, post-cardiac arrest care is delivered in an organized manner. Periodic review of processes is expected (the frequency is determined by organizations) to ensure that care and treatment align with current scientific literature. Note: For hospitals that use Joint Commission accreditation for deemed status purposes: Preprinted and electronic standing orders, order sets, and protocols that contain medication orders must meet the requirement MM.04.01.01 EP 15.

Tackling the new post-resuscitation care guidelines was a major focus of the DHS Inpatient Resuscitation Committee, a multi-disciplinary workgroup led by Dr. Sanko that includes CPR Committee leadership from all DHS hospitals. This group, which was established in 2019, has several goals. They include:

- Establishing and promoting expected practices in care for DHS hospital patients with acute, severe, and unanticipated clinical decompensation

- Serving as central reference for DHS for questions on in-hospital resuscitation care

- Homogenizing reporting so we can measure and improve

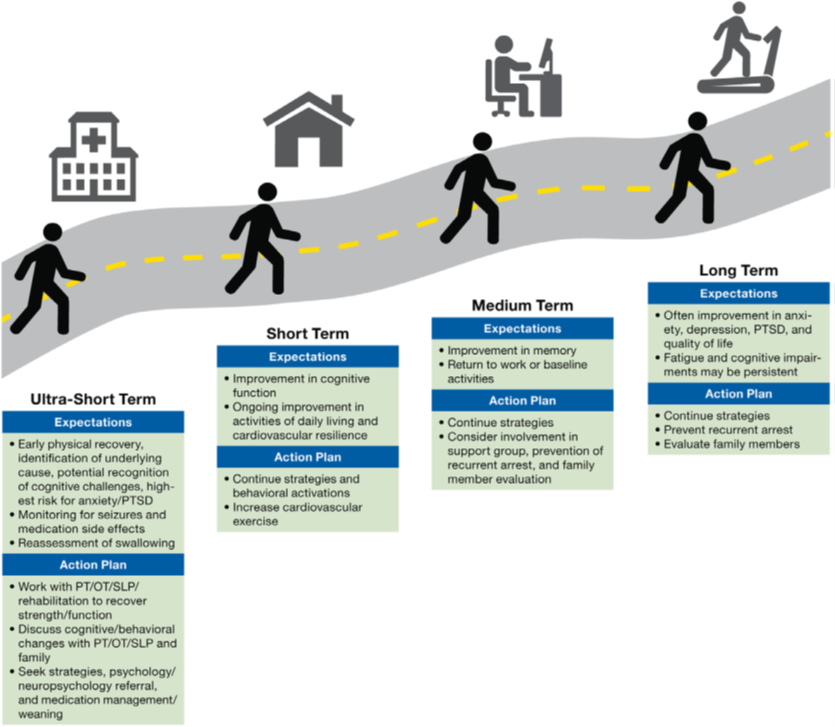

The workgroup developed a Code Feedback Form to use routinely for the evaluation of all resuscitation cases performed at the LAC+USC hospitals. It includes a section for neurologic status assessment at discharge as a baseline for post-resuscitation care. To help patients and families understand the goals and progression of post-discharge care, this chart was developed for the care team to discuss expectations and action-planning steps that will be key to patients’ optimum recovery.

Finally, Dr. Sanko’s “Take Home Points” stressed the benefits of high-quality management of in-hospital cardiac arrest:

- Increased process and patient-centered outcomes

- Improved neuro-intact survival

- Decreased length of stay among survivors

- Decreased costs of care over 30 days and one year

To achieve these benefits, hospitals will need:

- A dedicated CPR Committee with champions

- Prioritized data collection on in-hospital cardiac arrest/resuscitation

- Enrollment in a registry (e.g., AHA’s Get with the Guidelines)

A recording of the webinar is available online.