For the past decade, cases of congenital syphilis — a disease that occurs when a mother with syphilis transmits the infection to her baby during pregnancy — have risen in an unprecedented fashion.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that in 2021 the number of babies born infected with syphilis increased nearly sevenfold from 2012. Preliminary estimates also showed the number of infected babies to be at least 2,268; of those, 166 babies died. Babies born with congenital syphilis can face significant morbidity including brain and bone malformation, blindness, and organ damage.

What makes this epidemic even more devastating are the simple steps that can be taken to prevent transmission to the babies. If the pregnant person is diagnosed at least one month prior to delivery and receives the required doses of penicillin, the cure rate for both parent and baby is near perfect.

In California, testing for syphilis is required in the first trimester of pregnancy and strongly recommended in both the third trimester and at delivery. Studies have shown a link between structural barriers to prenatal care and congenital syphilis. These barriers include poverty, stigma about substance use during pregnancy, citizenship status, lack of health insurance, and low sexual health literacy.

A deep dive into the CHPSO database was undertaken to explore reports of congenital syphilis events from member hospitals and determine whether the structural barriers mentioned above were factors in these cases. Between 2020 and 2021, there were 106 cases reported in which pregnant patients were positive for syphilis during their pregnancy. Of these, 29 (27%) stated that the baby had congenital syphilis; for the other 77 cases there was no mention of the baby’s status.

Data from the CHPSO database suggested factors that could be contributing to the increasing number of babies diagnosed with congenital syphilis in member hospitals. Specifically, the results indicated a link between the following structural barriers and increased incidence of congenital syphilis:

- Pregnant persons not receiving prenatal care or having limited prenatal care appeared in 9% of the cases in which congenital syphilis was mentioned.

- Substance abuse appeared in 6% of the cases.

- Homelessness and citizenship status were each cited in 3% of cases.

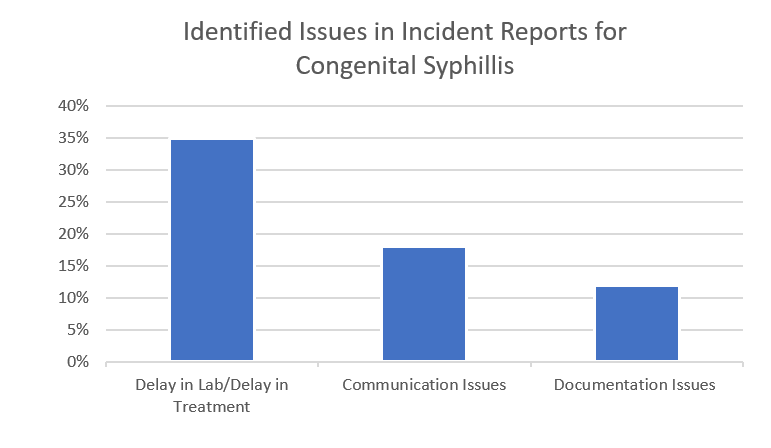

The data also provided insights on issues such as delays in labs/treatment, communication problems, and documentation failures that arise in the hospital when treating these babies that can be addressed to improve outcomes. An example of a case from the CHPSO database highlighting these structural barriers and hospital issues in caring for these patients is shown below.

“Patient [mother] had no prenatal care, was RPR+, THC+ and was held in L&D due to short staffing. The baby was born 0603 and was admitted at 1615. No septic work up or RPR titers w/ reflex were ordered or drawn for the baby. L&D RN stated that, ‘I left a call for pediatrician but she didn’t return it.’ L&D RN did not call back to receive orders, & delayed care.”

There is always room for improvement in the care of patients. When caring for pregnant people infected with syphilis and their potentially positive babies, the findings from the CHPSO database suggest that hospitals can improve in the areas of timeliness of labs/treatment, communication, and documentation.

Pregnant persons should have labs drawn and resulted as soon as possible to determine if treatment prior to delivery is necessary. When the pregnant person is determined to be positive, the timeliness of testing and treatment of the baby is vital to ensure a healthy outcome. Communication of results between providers and departments is necessary to ensure proper testing and treatment. Finally, results of any labs and testing should be documented and made available.

Evaluation of the CHPSO database provides an opportunity for us to offer suggestions on what steps should be taken to address this epidemic:

- Invest in testing, treatment, and prevention services

- Ensure early testing in pregnant patients

- Ensure repeat testing later in pregnancy

- Ensure quick and correct treatment of infection as soon as it is diagnosed

- Improve communication between lab and providers when ordering tests/reporting results