Despite hospitals’ commitment to patient-centered care, navigating the complexities of health literacy, cultural diversity, and language barriers presents a formidable hurdle, exemplified by the rising incidence of tuberculosis (TB) in California. The increasing prevalence of latent tuberculosis infection (LTBI) poses a unique concern, as individuals with LTBI are often asymptomatic and unaware, making early intervention crucial.

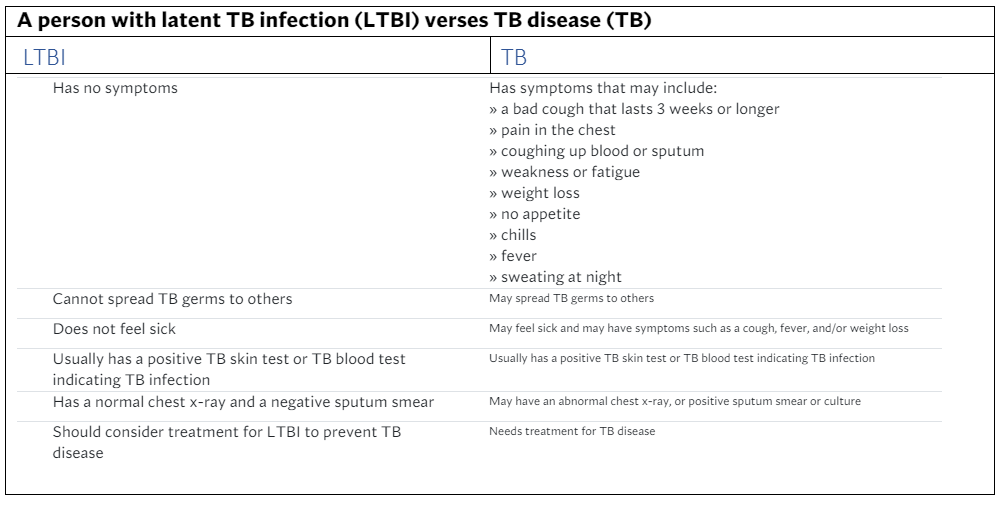

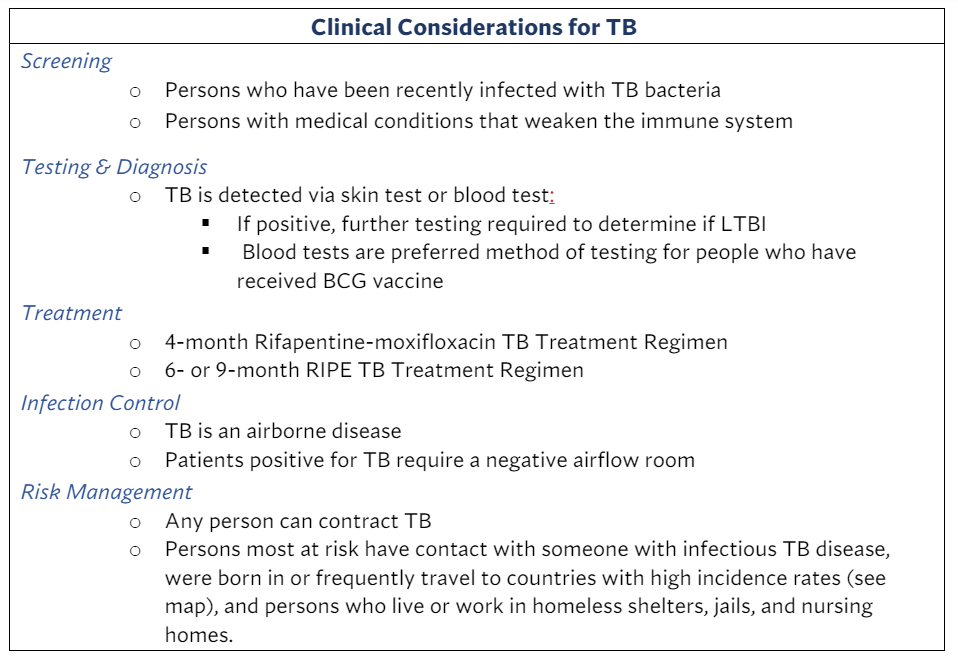

Across the globe, tuberculosis is the second leading cause of death related to infectious disease, second only to COVID-19. A bacterial infection that most commonly affects the lungs, tuberculosis kills one in six patients within five years of diagnosis. LTBI is a more insidious version of TB; it does not cause symptoms or make people feel sick, so the people who have it are mostly unaware and go untreated. People with LTBI cannot transmit TB germs. However, if the LTBI becomes active, the individual can transition from LTBI to TB disease. Treating LTBI is crucial for controlling TB and lowering the risk of progression from latent infection to active disease.

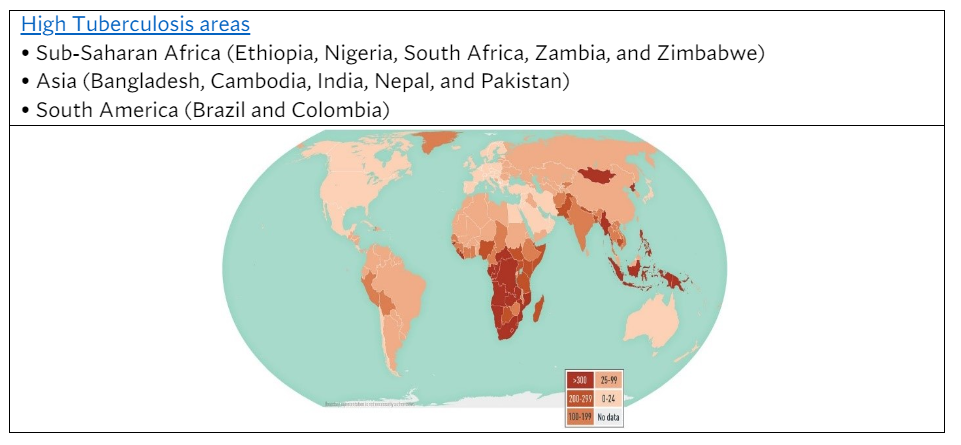

The challenge to provide quality care is exacerbated by the concentration of TB cases in high-risk areas such as Sub-Saharan Africa, Asia, and South America. When these patients receive treatment in California hospitals, they are labeled among broad ethnic categories which can lead to misidentification for health considerations. For example, studies have shown differences in liver enzyme concentrations among ethnic groups that can impact drug therapy regimens. Inaccurately recording or categorizing patients’ ethnic and racial backgrounds can compromise the quality of health care they receive. Studies suggest broad ethnic categories may obscure pertinent health variables essential for tailored treatment.

TB notably affects Asians. Asians as a racial and ethnic category encompass a diverse mix of backgrounds such as Laotians, Chinese, Vietnamese, Filipinos, and Southeast Asians from India. Non-U.S.-born Asian patients may face language barriers hindering effective communication and accurate symptom presentation. Studies have shown that, when compared to their white counterparts, Asian patients were less understood and less involved in their health care decision making. Some Asian cultures were indicated as more likely to live in a three-generation household, adding a layer of complexity when an infectious person resides with vulnerable older adults or children. Children are especially vulnerable to TB and may experience delayed diagnoses due to overlapping symptoms with various common cold like illnesses.

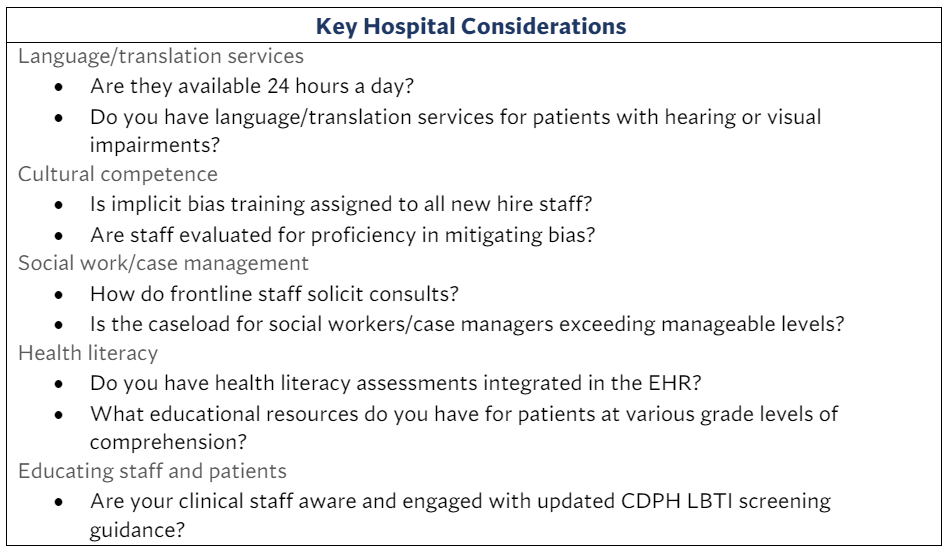

Cultural variations in personal health practices, coupled with diverse linguistic backgrounds, contribute to treatment adherence issues, potentially leading to hospital stays, readmissions, and suboptimal health outcomes. This is a particular challenge to hospitals because half of the people with TB require hospitalization, incurring costs twice as high and stays four times longer than for other conditions; the average length of stay is 11 days. Hospitals must navigate these intricacies, promoting cultural competence among staff, fostering an inclusive environment, and facilitating effective cross-cultural communication. Addressing dietary needs, religious practices, and respecting diverse backgrounds are crucial elements in providing holistic care.

Despite LTBI predominantly affecting those from outside the U.S., California grapples with a disproportionately high incidence rate, demanding a renewed focus on contemporary, user-friendly measures that support patient-centered care for TB and LTBI populations.

Recent increases in reported TB cases prompted the California Board of Registered Nurses to alert licensed nurses about updates to screening guidance.

Hospitals must adapt to the evolving health care landscape, considering immigration trends and travel seasons. Hospitals with bilingual staff proficient in cultural competence, alongside diversity and inclusion efforts, are in the best position to care for LTBI patients. In an era of global interconnectedness, infectious diseases know no boundaries — this emphasizes the need for vigilant health care strategies. With 2,000 Californians diagnosed with TB annually, hospitals must prioritize comprehensive and adaptable approaches to meet the unique needs of diverse and linguistically varied patient populations.