Over the past several decades, the United States has experienced a rising crisis in substance abuse. This is illustrated most dramatically by the rise in deaths from drug overdose.

According to the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) and Prevention, the number of drug overdose deaths has quadrupled since 1999 [i]. More work needs to be done to prevent the misuse of prescription opioids, prevent the use of illicit opioids, and improve the treatment of opioid use disorder.

In February, CHPSO and HQI had the opportunity to host a webinar with three California Bridge Program advisers who have made it their mission to advocate and educate health care providers on evidence-based treatment for substance use disorders. The panelists included Tana Brookes, RN, a nurse adviser with more than eight years of clinical nurse experience who is currently practicing as an emergency department charge nurse; Chenin Kenig, a nurse practitioner (NP) special adviser with more than 14 years of clinical experience who is currently practicing as a NP in the emergency department; and John Bressan, a NP special adviser with more than 18 years of clinical experience, currently practicing as a NP in the emergency department.

Bressan began the webinar by discussing how providers should approach substance use addiction. He highlighted that it should not be viewed as a moral failing, but rather as a chronic disease that requires medical treatment. Relapse should be viewed as normal and expected. The goal of providers should be to help reduce craving and withdrawal symptoms, which in turn will reduce drug-related overdose deaths, disease, and violent crimes and improve treatment outcomes.

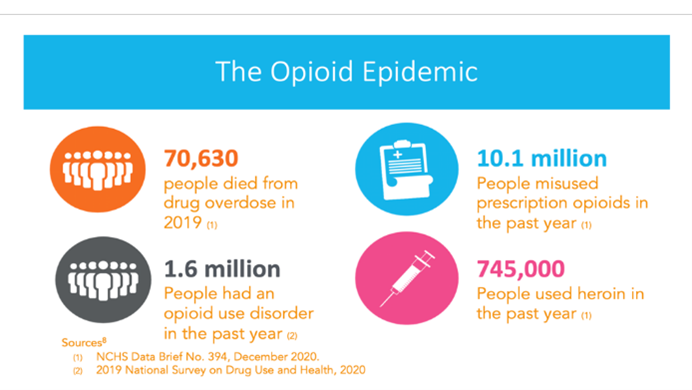

Bressan also shared alarming findings regarding drug overdose deaths, misuse of prescription opioids, and the number of people living with opioid use disorder.

Bressan then discussed subjective signs and symptoms for providers to look for when attempting to identify a patient suffering from opioid withdrawal. Common subjective signs and symptoms may appear flu-like. These include patient complaints of agitation, body aches, nasal congestion, abdominal cramping, fever, or chills. He points out that with COVID-19 and flu, body aches are a common complaint, and it is essential for providers to sift through these subjective findings. Common subject findings include the patient being unable to sit still in the chair or bed, being quick to anger, or experiencing tachycardia, diaphoresis, dilated pupils, rhinorrhea, vomiting/diarrhea, yawning, and/or piloerection.

Brookes then discussed the benefits of using medication for addiction treatment. These benefits included decreased cravings, decreased use of elicit opioids, decreased serious bacterial and viral infections, decreased overdose, decreased all-cause mortality, increased quality of life, and increased community health. Unfortunately, historically, medication assisted treatment has only been available in very limited treatment centers. The California Bridge Program (see details on the program below) is advocating for starting treatment in the emergency department (ED) and has had much success following this model of care.

Brookes identifies barriers patients with substance use disorder (SUD) often face, which include traveling long distances to access care, long wait times, behavioral health requirements, and stigma from the health care community. There is significance for the ED, as these providers are often the only time patients with SUD interact with health care providers and the only places they seek care. Brookes mentioned that 28% of adult patients in the ED screen positive for SUD.

Kenig then presented several studies providing evidence supporting the use of medication for substance addiction treatment. Not surprising, there is a short-term increase in mortality risk post-ED discharge for patients with SUD. Weiner et al. (2019) conducted a study in Massachusetts over five years that examined overdose patients who were discharged from the ED without any treatment [ii]. Results from this study showed that 20% of those who died after discharge from the ED died within the first month [ii]. Furthermore, of those who died within the first month after discharge from the ED, 22% died within the first two days [ii]. This study highlights how vulnerable these patients are in the moment when they come to the ED.

Number of deaths after ED treatment for nonfatal overdose by number of days after discharge in the first month (n=130)

D’Onofrio et al. (2017) published results from their study where they randomized ED patients presenting with opioid withdrawal into one of three treatment arms [iii]. The first treatment arm was referral to a treatment program. The second treatment arm was brief counseling intervention followed by referral. The third treatment arm was initiation of buprenorphine, followed by counseling and referral. Findings showed that those patients started on buprenorphine in the ED had a near-doubling in 30-day treatment retention and less than half of the self-reported rate of opioid use. This highlights the significance of this evidence-based medicine treatment and dispels the myth that patients do not desire treatment. Being able to offer this option to ED patients who may not even know it is available to them can change the course of their lives.

The panelists described the major features of buprenorphine, a safe and effective treatment for opioid use dependence (OUD) withdrawal, cravings, and overdose. It is a partial opioid receptor agonist that has a ceiling effect on respiratory depression and sedation, but not on analgesia. Buprenorphine has a high affinity, which means it blocks or displaces other opioids and can precipitate withdraw. Due to this, Bressan stressed the importance of assessing these patients to make sure that they are in opioid use withdrawal or else it could potentially precipitate withdrawal symptoms. He continued by stating that if the patient is not exhibiting withdrawal symptoms, but the provider suspects that they will soon, the patient could be sent home with a home starter kit or be instructed to return to the ED when they start to experience withdrawal symptoms.

Any provider with a DEA license can order buprenorphine to be administered in the ED; however, to prescribe this medication to an outpatient, the provider must obtain a DEA X-waiver, an additional qualification that allows the provider to prescribe buprenorphine for the purpose of addiction treatment, and not for pain management. Obtaining an X-waiver used to be a significant barrier for many providers; however, in January 2021, in response to the growing opioid epidemic, government officials changed the steps necessary to obtain the X-waiver by removing the time-consuming education requirements. Now, providers can apply online by answering a few questions and expect to receive their X-waiver within a few weeks.

Brookes touched on the concern that some providers feel they are just replacing one drug for another by administering buprenorphine to patients who use opioids. This concern can be eliminated when the provider approaches the treatment of SUD as a chronic disease. She uses the example of a person who has diabetes and needs to take insulin to treat their condition. Just like insulin for a diabetic, buprenorphine is a stabilizing medication for an individual with OUD. Due to buprenorphine’s ceiling effect on euphoria, it is not a medication patients use recreationally but rather to treat symptoms of cravings and withdrawal and many patients will state that they finally feel “normal” when using it for OUD. Brookes also pointed that due to buprenorphine’s high affinity, it protects the patient from overdose and can prevent death if they were to use opioids.

What is the California Bridge Program and how is it revolutionizing the system of care?

California Bridge is a program of the Public Health Institute, which promotes health, well-being, and quality of life for people throughout California, across the nation, and around the world. The goal of the program is to treat patients with substance abuse disorder in a non-judgmental, caring manner utilizing evidence-based medicine. In 2021, the CA Bridge model was implemented in 164 hospitals. To date, CA Bridge has had 76,267 Substance Use Navigator encounters, 42,641 patients identified with OUD, and 24,978 encounters where medication assisted treatment was prescribed or administered. By 2025, CA Bridge hopes to provide 24/7 access to high-quality substance use disorder treatment in all California hospitals.

The CA Bridge model has three pillars:

- Low barrier for treatment. This is done by making medication for addiction accessible in the ED and all hospital departments without complicated restrictions and procedures. Barriers cause patients to leave against medical advice, not seek care in the future, and put them at higher risk.

- Connection to care and community. This can be done by linking the patient to ongoing care through active support and follow-up utilizing substance use navigators, who help coordinate care and bridge the gap between the patient and care team.

- Culture of harm reduction. This is achieved by creating a welcome culture in hospitals that does not stigmatize SUD and builds trust through human interactions. It also involves utilizing person-first language, such as “person who uses drugs” instead of “addict,” “user,” or “junkie.” This is fundamental to the start of providing care without judgment and building connections with patients.

How providers can help

There are three easy steps providers can take to impact the overdose crisis:

- Sign up for an X-waiver. Registration can be done online.

- Spread the word and encourage all providers to sign up now.

- Treat patients and save lives. The California Bridge Program is here to help and is a great resource for updated guidance, training, and related resources.

[i] https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/epidemic/index.html

[ii] Weiner, S. G., Baker, O., Bernson, D., & Schuur, J. D. (2020). One-Year Mortality of Patients After Emergency Department Treatment for Nonfatal Opioid Overdose. Annals of emergency medicine, 75(1), 13–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annemergmed.2019.04.020.

[iii] D’Onofrio, G., Chawarski, M. C., O’Connor, P. G., Pantalon, M. V., Busch, S. H., Owens, P. H., Hawk, K., Bernstein, S. L., & Fiellin, D. A. (2017). Emergency Department-Initiated Buprenorphine for Opioid Dependence with Continuation in Primary Care: Outcomes During and After Intervention. Journal of general internal medicine, 32(6), 660–666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-017-3993-2.